Dr. Ottó Toldi [1] and Dr. Yinghao He [2]

[1] MCC Climate Policy Institute, Budapest, Hungary

[2] Belt and Road & Global Governance Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

1. Introduction

In September 2020, the government of the People's Republic of China committed itself in the general debate of the 75th United Nations General Assembly to plateauing carbon emissions by 2030, and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060.

There is clear evidence that these ambitious goals are being pursued. For instance, China is adding as much new renewable capacity to the electricity grid as the rest of the world combined. In 2020 alone, the expansion of wind and solar capacity was three times larger than that in the United States.

And yet, simultaneously, as the world’s most populous country (1.412 billion people in 2022, 17.64% of the world’s population), and with a fast growing economy (China’s GDP grew by an average of 8.9% a year between 2010 and 2019), China remains both the world’s largest producer and consumer of energy, and not all its energy needs can be met by renewables. While the country accounts for 26% of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, 64% of these emissions currently derive from an electricity sector based on coal-fired power plants, with capacity continuing to be added, which does nothing to further the 2030 and 2060 goals.

A global pandemic, two wars, and trade disputes with the United States, have simultaneously made energy prices and supply chains less predictable and more costly, with the result that in 2021 and 2022, China faced an energy shortage. Under these real pressures, the ideal of greening the economy has lost further ground as a policy priority. Perhaps understandably, what is desirable is being treated as secondary to what is necessary.

This chapter discusses how China is attempting to maintain both these priorities – greening the economy, and securing its energy supply – as circumstance throw them into increasing conflict. To this end, Section 2 provides a background on China’s energy policy. Section 3 then details the use of the main types of fuel in China. Section 4 concludes by outlining the prospects for future energy usage in China, and in the context of this, the prospects of the Chinese greening agenda.

2. Background

On June 13, 2014, the sixth meeting of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission proposed a new energy security strategy called the “Four Revolutions and One Cooperation”. This strategy includes promoting an energy consumption revolution to curb unreasonable energy use, advancing an energy supply revolution to establish a diversified supply system, driving an energy technology revolution to facilitate industrial upgrades, advancing an energy system revolution to streamline energy development, and comprehensively strengthening international cooperation to achieve energy security under open conditions.

In 2016, the National Development and Reform Commission and the National Energy Administration issued the “Energy Production and Consumption Revolution Strategy (2016-2030)”, which defined the content of the energy consumption revolution in five aspects: firmly controlling total energy consumption, creating a medium to high-end energy consumption structure, deeply advancing energy conservation and emission reduction, promoting the electrification of urban and rural areas, and fostering a consumption culture of thrift and saving.

In 2021, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the “Opinions on Improving the Accurate and Comprehensive Implementation of the New Development Concept to Achieve Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality”, further clarifying the need to integrate energy conservation throughout all aspects and fields of economic and social development. Meanwhile, China launched its 14th five-year plan until 2025 (National Economic and Social Development Plan), outlining the country’s key economic and social goals for the next half decade.

The energy-related goals of the Plan were as follows:

- To increase and develop the country’s technological, innovative, and production capabilities in the field of energy, with particular regard to making renewable production more efficient, cost-competitive, and reliable;

- To establish hydrogen as a key priority, in terms of bothdecarbonization and energy storage;

- To innovate in relation to fossil fuels and nuclear energy, in order to increase the efficiency of resource use;

- To prioritize China’s low-carbon and carbon-neutral initiatives: greenhouse gas emissions should plateau by 2030, and climate neutrality should be achieved by 2060;

- To set goals for increasing non-fossil-fuelled, decarbonized energy sources, with a ratio of 20% of primary energy consumption and 39% of total (electricity, heat) energy production by the end of the Plan’s period;

- To increase energy efficiency and renewable energy use related to buildings. The tools for this are the development of environmentally friendly buildings with almost zero energy requirements, and primarily the increase of photovoltaic (PV) capacities installed on new buildings, which according to the Plan, will exceed 50 GW by 2025.

Additionally, and unlike the previous one, the current five-year plan set no fixed upper limit for coal consumption, but the achievable share of technologies that can ensure system-level flexibility (24%) and demand-side response capacities (3%-5% of the maximum load) was quantified.

3. Energy Use in China

China’s energy resources are characterized by a scarcity of oil, limited natural gas, and relatively abundant coal. Considering the reliable substitution process of non-fossil energy, the fundamental national condition of "coal being the mainstay" will not change in the short term.

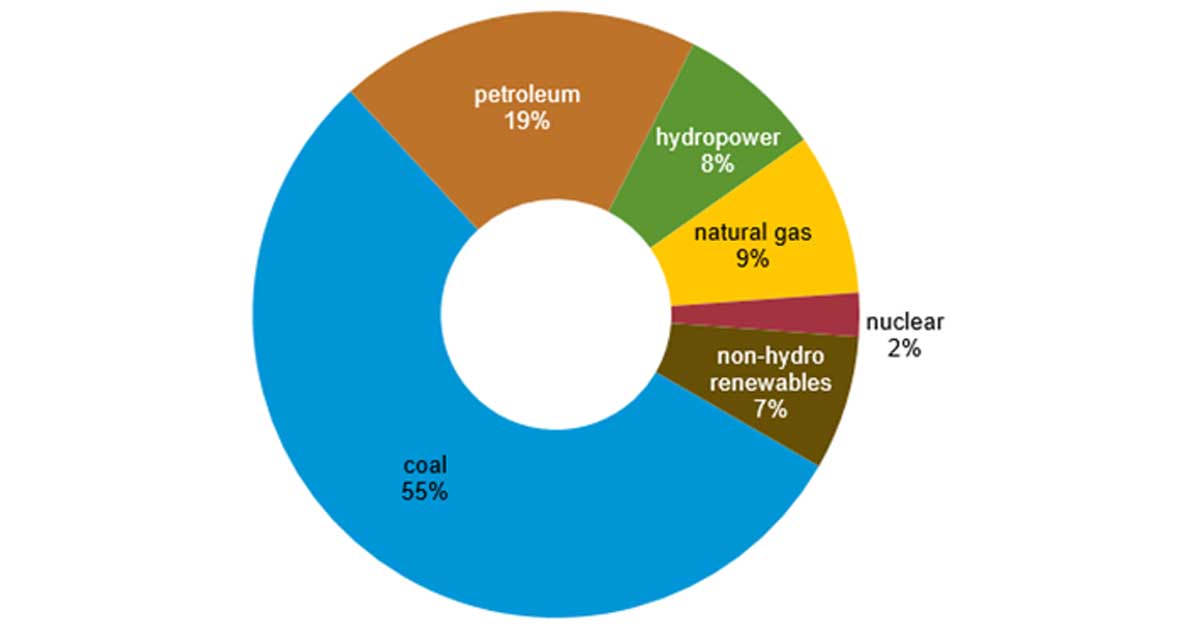

In 2022, coal accounted for about 55% of China's total energy consumption, down from 70% in 2001. Crude oil and its refined products, liquefied coal and methanol produced by clean coal technologies are the second largest sources of fuel. Although China has diversified its energy supply and replaced some oil and coal use with cleaner fuels in recent years, cleaner energy sources (hydroelectric 8%, natural gas 9%, nuclear 2%, other renewables 7%) made up a relatively small share of China's energy mix even in 2021 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - China's primary energy consumption in 2022. Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2022

3.1. Liquid Fuels

In 2021, China was the world's fifth largest producer of liquid energy carriers (petroleum, liquefied coal, methanol produced from coal), with production reaching 5 million barrels per day, compared to daily consumption of 15.3 million barrels per day. Almost 80% of the total liquid energy production came from crude oil and its refined derivatives, and the remaining part came from the conversion of liquefied coal and methanol produced from coal into biofuel.

The largest share of oil products consumed since 2000 was diesel (24%) and gasoline (23%). Interestingly, the growth rate of oil demand in the transport sector has been decreasing since 2015, the main reasons for which are:

- quarantines and economic shutdowns due to Covid-19;

- economic slowdown due to other reasons;

- stricter environmental protection measures;

- restriction of urban vehicle use;

- greater prevalence of alternative propulsion vehicles (electric vehicles, vehicles running on compressed natural gas, and lorries and trains running on liquefied natural gas);

China's battery electric, plug-in hybrid and fuel cell electric vehicle purchases set records in 2021 and 2022, with sales up 181% compared to 2020. China has introduced national fuel emission standards in line with Euro 6, which will be fully implemented by 2030.

China is trying to make profitable and diversified use of its vast coal reserves by turning some of the coal into liquid fuel to replace crude oil. Coal liquefied petroleum gas (CTL) production was estimated at 124,000 bpd and methanol production at approximately 508,000 bpd in 2021.

After the Chinese government confirmed in May 2022 - two months after the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war - the importance of domestic crude oil exploration and production, China's National Energy Agency set a domestic crude oil production target of 1,5 billion barrels million tons per year by 2022, which corresponds to a daily 4.1 million barrels (565,800 tons) of production. This is a 2% increase compared to 2021.

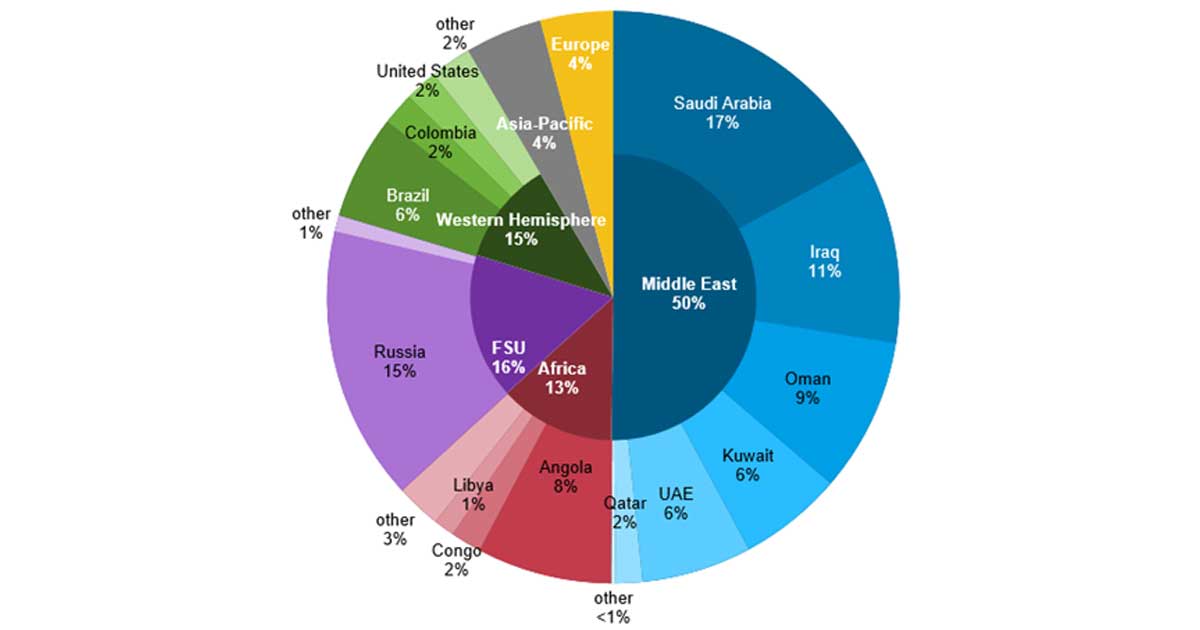

In recent years, China has diversified its sources of crude oil imports, with Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar and Oman playing the most important role. As of 2017, China became the world's largest crude oil importer, with imports reaching 10.3 million barrels per day in 2021 (Figure 2). Given the current geopolitical situation, an interesting development is that crude oil imports from the United States have significantly decreased from an average of 481,000 barrels/day in 2020 to 248,000 barrels/day in 2022, and that China's oil imports from Iran have increased significantly despite UN/US sanctions.

3.2. Gaseous Fuels

China has significant natural gas reserves. Based on 2021 estimates, the amount that can be extracted is 6,654 billion m3, which would be enough for roughly twenty years based on the current annual consumption of 379.2 billion m3. However, most of the reservoirs have low permeability and porosity, and shale gas extraction does not seem to be simpler either. Even today, only a few such projects are underway, despite the government's push for the development of these resources. Despite the unfavorable conditions, China's domestic natural gas production has steadily increased over the past few years. China's 14th Five-Year Plan and the 2022 Energy Works Guidance targeted 229 billion m3 of extraction by 2025.

Figure 2 - Diversification level of China's crude oil imports in 2021. Source: Global Trade Tracker

Figure 2 - Diversification level of China's crude oil imports in 2021. Source: Global Trade Tracker

China's natural gas production continues to rise, reaching 207.58 billion cubic meters in 2021, a year-on-year increase of 7.8%. The average annual compound growth rate during 2012-2021 was 7.3%. In 2022, China's natural gas production reached 220 billion cubic meters, a year-on-year increase of 5.98%.

China's natural gas consumption reached 369 billion cubic meters, accounted for 9% of total energy consumption in 2021. It is typical of the dynamics of consumption that between 2011 and 2021 the demand for natural gas increased by an average of 11% per year. China thus became the world's third largest consumer of natural gas, behind the United States and Russia.

Several factors have contributed to the increase in natural gas consumption in recent years. Poor air quality (especially in urban areas of northeastern China, where increased coal use in winter causes smog and dangerous levels of pollution) has prompted the government to accelerate the transition from coal to natural gas for both industrial use, power generation, and residential - commercial use. Another driver of the increase in natural gas consumption was the decrease in the availability of hydropower, in addition to a cold winter and a warmer-than-average summer, which increased residential electricity demand. Increased industrial production also contributed to the increase in annual demand. China's transition from coal to gas in the heating segment was an important factor in the increase in demand for natural gas. China's Clean Winter Heating Plan has set a goal of 70% clean heating through natural gas or electric boilers from 2017 to 2021. In 2020, the Ministry of Ecology and Environmental Protection set the goal of switching more than 7 million households from coal to natural gas in 28 Northern cities.

China has diversified its LNG suppliers in the past few years, and Australia has become its largest supplier, accounting for 40% of LNG imports, followed by the USA until the Russo-Ukraine war. However, in 2023, China imported the most LNG from Australia, with an import volume of 24.16 million tons, accounting for 33.88%. Then came Qatar, with an import volume of 16.66 million tons, accounting for 23.36%. Russia ranked third, with an import volume of 8.05 million tons, accounting for 11.29%. Malaysia ranked fourth, with an import volume of 7.09 million tons, accounting for 9.94%.

In 2022, China had 23 LNG regasification terminals with a combined capacity of 135.8 billion m3. However, in 2024, an additional 102 billion m3 of LNG import terminals are expected to go online.

For piped natural gas imports, China mainly imports through three onshore natural gas pipelines, namely the Central Asia Natural Gas Pipeline A/B/C, the China-Russia East Line Natural Gas Pipeline, and the China-Myanmar Natural Gas Pipeline.

In 2023, China's piped gas imports from Turkmenistan are estimated to be 33.06 billion m3, accounting for 51%; Russia is estimated to be 21.73 billion m3, accounting for 33.3%; Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are estimated to be 6.46 billion m3, accounting for 10%; Myanmar is estimated to be 3.6 billion m3, accounting for 5.6%. In 2014, China and Russia signed a 30-year natural gas agreement, according to which China imports an average of 36 billion m3 of natural gas annually from Gazprom's fields in East Siberia via the Power of Siberia-1 pipeline. This agreement was amended at the beginning of 2022, so that the annual imported volume will be 46.7 billion m3. The shift of the center of gravity of Russian gas exports to Asia did not start recently. Power of Siberia-1 is currently 3,000 km long, but after its full construction, its length will increase to 6,500 km, and its capacity will eventually reach 61 billion m3. The construction of the Power of Siberia-2 pipeline with an annual capacity of 50 billion m3, which also supplies Mongolia, will start in 2024.

Looking to the future, next to renewables, the use of natural gas is growing at the fastest rate in China, the demand for which has quadrupled in the last decade. In 2023, China's natural gas consumption reached 391.9 billion cubic meters, an increase of 28.9 billion cubic meters from 2022, a growth rate of 8%. The growth of the natural gas sector is critical to China's efforts to reduce dependence on coal, thereby significantly reducing air pollution and CO2 emissions. By 2040, By 2040, China's annual natural gas consumption peak will reach 650 billion m3, which is 2.3 times the 280 billion m3 in 2018. We mentioned above that China's natural gas consumption accounted for 9% of the total final consumption in 2021, which it intends to increase to 15% by 2030. Moreover, relevant Chinese policies and diplomatic initiatives emphasize supply diversification in order to strengthen energy security in the future, due to the energy crisis and war conflicts.

The fact that in some places natural gas replaces some of the coal-fired power plants in the eastern part of the country, where the energy demand is higher than in the rest of the country, and in the northeastern region, where the tightening due to environmental regulations, the growth of coal-based energy production gradually slowing down. Natural gas is gradually gaining an increasing share in the electricity mix, but in 2020 it still accounted for less than 3% of total production.

3.3. Solid Fuels

China's coal production reached 4.56 billion tons per year by 2022 thanks to continuously improved extraction technologies. With this, they were able to increase the efficiency of extraction, which also increased by closing the smaller, old mines. The increase in efficiency is also part of the expansion of long-distance railway capacity related to mining, an example of which is the Haoji Railway, which opened in October 2019, and whose task is to connect the internal coal production centers with the eastern demand centers.

In 2020, the electricity sector accounted for nearly 61% of China's coal consumption, with industry (steel and cement production) and residential heating accounting for the rest. China's demand for coal is expected to be reduced by the expansion of renewable and nuclear energy capacities, and the partial replacement of coal with natural gas will have the same effect. But China's carbon dioxide reduction targets and programs, such as the plan to introduce a national emissions trading system, will also have a demand-reducing effect. According to the formulation of China's energy policy, despite the above, coal remains the primary component of China's primary energy mix as a guarantee of energy security.

It is interesting that, in addition to the World's leading domestic production, China is also the World's largest importer of coal, with an annual volume of 357 million tons. In 2023, China imported a total of 474.399 million tons of coal (about 474 million tons), an increase of 181.079 million tons year-on-year, a growth of 61.8%. The increase in imports was a response to electricity shortages across the country and rising domestic coal prices. The largest source of imports is Indonesia with 60% of total imports. Indonesia's low-quality and cheap coal can be mixed well with high-quality Chinese coal. Russia (18%) and Mongolia (5%) are next in the list of import locations, ahead of Australia.

3.4. Atomic Fuel

In the past, the Chinese nuclear energy sector was characterized by the domestication of various technologies that existed in the World, from which, by adopting and combining the details they considered appropriate, their own technical solutions and their own nuclear industry products were gradually developed.

In 1998, the project related to the Canadian CANDU reactors started at the Qinshan Nuclear Power Plant, in 1999 the construction of the Russian VVER-1000 reactors at the Tianwan Nuclear Power Plant began, in 2007 the negotiations with the French company Areva on the construction of EPR reactors began, and then the Westinghouse AP1000 reactors were to follow. After the bankruptcy of the company in 2017, in 2019 they decided to use China's own technology instead of AP1000 and build Hualong One. Since then, China has been independently developing fourth-generation nuclear power plants and small modular reactors, and is even building an experimental fusion reactor.

In recent yearsdue to growing concerns about air quality, climate change, and fossil fuel shortages, nuclear power plants are seen as a long-term alternative to coal-fired power plants as the typical base-load power plants that generate base-load electricity.

Although nuclear generation is a small part of the total power generation portfolio, China generated approximately 366 TWh net of electricity in nuclear power plants in 2020. This accounted for approximately 5% of total production, an 11% increase compared to 2019. On nuclear power, China has approved the construction of six nuclear reactors in 2022, a step towards its goal of increasing nuclear capacity to 70 GW by 2025 and between 120 GW and 150 GW by 2030, up from 55 GW in 2021 compared to installed capacity.

China currently ranks third in the world in terms of both total installed nuclear power capacity and the amount of electricity produced in nuclear power plants, accounting for about one-tenth of global production. As of February 2023, China had 55 nuclear power units operating with a capacity of 57 GW, 22 under construction with a capacity of 24 GW, and more than 70 units with a capacity of 88 GW under construction. The 2020 National People's Congress supported the future construction of 6-8 reactors per year, reaching an installed capacity of 200 GW by 2035.

China aims to achieve complete independence along the nuclear value chain, including nuclear power plant construction, independent development, fuel production, radioactive waste management and recycling, and fusion technology development.

3.5. Renewable Fuels

Renewable projects generated more than 2,200 TWh of net electricity in 2020, an 11% increase over 2019 levels. In 2020, most of the world's wind-based electricity generation, about 471 TWh, was in China. Solar energy is the fastest growing source of electricity generation in China. The net production in 2020 was 270 TWh, 21% more than in 2019. Most of the solar equipment used worldwide is manufactured in China. As an inherent part of development, it has become timely to take and implement measures aimed at improving network development and the flexibility of the transmission system in order to facilitate the integration of weather-dependent renewables into the network. The Chinese government's goal in the 14th five-year plan is to have at least 570 GW of solar and wind-based power generation capacity in the period 2021-2025, and a minimum of 1,200 GW by 2030.

4. Energy in China: Future Prospects & Vision

China is characterized by a strange duality. Greening at a dramatic rate on the one hand, and switching cleaner natural gas back to coal on the other.

China electrical grid generated about 8,360 terawatt hours (TWh) of net electricity in 2021, 760 TWh more than in 2020. In absolute terms, the Chinese grid uses 61% of China’s mined coal, and thus accounts for 14% of global carbon emissions – more than the United States total emissions, which constitute 12% of the global total.

Relying on coal-fired power plants for two-thirds of its electricity, China emits more greenhouse gases each year than any other country. It is 26% of global emissions, two-thirds of which comes from the Chinese electricity sector.

China is adding new renewable capacities to the grid as fast as the rest of the world (EU, USA, India) combined (Figure 3). In 2020 alone, there were three times as many wind and solar capacity additions as the United States in the same year. In the first half of 2022, it invested an additional $100 billion in solar and wind energy, and this trend will continue in 2023.

Figure 3 - Renewable capacity expansion in China, the European Union, the United States and India 2019-2023. Source: IEA

In fact, new research has shown that China could reach 80% of carbon-free electricity generation as early as 2035 without increasing cost or security of supply risk (N. Abhyankar et al., 2022). However, high import energy prices due to the Russian-Ukrainian and Middle East wars has made China to reassure the main contradiction, which leads to the slow-down.

„China has vast resources and advanced renewable supply chains in renewable energy utilization. China produces roughly 75% of the global supply of solar panels and batteries, as well as around 60% of key components for wind turbines. In response to the need for a global clean energy transition, China's mining and metal industry is doing its best to meet domestic and foreign demand” as as found by M. O'Boyle (2023). Due to renewable industry and the greening of transport, the demand for cobalt alone will increase fivefold by 2030. Demand for lithium is expected to increase 18-fold by 2030 and 60-fold by 2050 thanks to e-mobility campaigns. 68% of nickel, 40% of copper, 59% of lithium and 73% of cobalt are extracted from mineral ores in China or by companies with Chinese interests. 70% of the cathodes and 85% of the anodes of lithium ion batteries are manufactured in China. As well as 66% of separators, 62% of electrolytes and 78% of batteries. China is also the largest consumer of the above products.

As part of the implementation, plans include increasing the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to 25% and increasing the total wind and solar power capacity to 1,200 GW by 2025. Regardless, China's 14th Five-Year Plan considers the energy utilization of coal still necessary in the coming years in order to increase energy security and economic efficiency.

Since the international community is placing more and more emphasis on environmental and climate protection, technologies with which fossil energy carriers can also be used cleanly are coming to the fore. It is expected that there will be huge demand from the natural gas and coal sectors for the so-called emission-minimizing clean coal technologies (anaerobic gasification, polygeneration, petrochemicals, CCUS, methanol economy, DAC) in the future. However, CCUS is still a developing technology that needs to be transformed into a market-level industry. According to the annual report entitled „China CCUS report 2023”, under the goal of achieving carbon peak in 2030 and carbon neutrality in 2060, China's CCUS emission reduction demand is: about 24 million tons/year in 2025 (14-31 million tons/year), which will increase to nearly 100 million tons/year (0.58-147 billion tons/year) in 2030, and is expected to reach about 1 billion tons/year (885-1.196 billion tons/year) in 2040, and will exceed 2 billion tons/year (1.87-2.245 billion tons/year) in 2050, and about 2.35 billion tons/year (2.11-2.53 billion tons/year) in 2060.” Accordingly, in the coming decades, China also sees the construction of CCUS facilities as an important task.

4.1. The energy trilemma (security of supply, decarbonization, affordability)

The global problems of the past few years that also affect the economy (Covid emergency, Russian-Ukrainian and Middle East wars, trade disputes with the USA and the EU) have caused unexpected disruptions in the global energy supply chain, and resulted in rapidly fluctuating energy prices. In China in 2021 and 2022, there was also an energy shortage, partly due to the above, partly due to extreme weather. It seems that the aspects of greening can be ranked further back, in the order of goals, since it seems that the policy would like to return to the old and familiar, well-functioning, but less sustainable tools for dealing with challenges. There are already plans to build new coal-fired power plants and increase domestic fossil fuel extraction, which, however, will not be sustainable in the long term, either from the point of view of environmental protection, climate protection, or human health.

China approved the construction of more coal power plants last year than at any time in the past seven years, despite the government's promises and goals. “In 2023, China's newly started coal-fired power plant capacity reached 70.2 GW, four times that of 2019. In the same year, China approved 114 GW of coal-fired power plant capacity, a 10% increase from the previous year. The cumulative approved capacity in two years reached 218 GW, equivalent to the electricity demand of the entire Brazil. According to the 14th Five-Year Plan, China's coal-fired power plants will retire 30 GW in 2025, but only 9 GW has been retired in the past three years.”

4.2. Understanding China’s commissioning of new coal-fired power plants

A crucial question is what is driving the recent wave of permits for new coal-fired power plants at the beginning of the er of renewable energy. According to the authors of the report, one of the reasons can paradoxically be traced back to climate change. Due to the continuous drought and last summer's historic heat wave, the sale and electricity consumption of air conditioners increased greatly, and at the same time, significant hydropower plant capacities also fell out of system control due to the drought. Due to the heat and drought, rivers have almost dried up, including parts of the Yangtze, which normally has plenty of water. In the heat, the performance of solar and wind power plants also decreased, China simply had nothing to touch.

Added to all of this, the high price of liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports is also expected to slow down the implementation of China's natural gas goals in the coming years.

However, according to some analysts, the approval of new coal power projects did not come out of nowhere. The messages of the coal sector and the electricity providers during periods of energy shortages have always been about the fact that the cheap domestic coal reserves are still a sure guarantee of energy security, and solutions for the future should be sought based on this.

There are some reasons I thought regarding for China building coal-fired power plants:

- China’s main concern is about energy security. China experienced power shortages in 2022, mainly due to the instability of the power grid's reliance on renewable energy generation. As a result, China has adopted a multi-pronged strategy to enhance the stability of its power supply. Addtionally, China emphasizes that both renewable energy and coal-fired power plants should have "sufficient capacity" to provide electricity, providing dual capacity guarantees for the stable operation of the power grid.

- Building modernizing coal plants for future green transformation. Some of the new coal-fired power plants are more efficient and less polluting than older ones. Modern coal plants can serve as a transitional technology, potentially reducing overall emissions compared to older plants while renewable capacity is being scaled up. Using 2005 as the base year, the reduction in coal consumption for power generation from 2006 to 2021 resulted in a decrease of approximately 8.9 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions, contributing 41% to the carbon reduction efforts of the power sector. With technological advancements, China's coal-fired power plants are expected to achieve ultra-low emissions or near-zero emissions, comparable to clean natural gas power generation.

5. Conclusions

Whether China can meet its decarbonization goals depends largely on the ability of policymakers and industry to reduce the country's dependence on coal. Over the past decade, coal's share of final energy consumption has fallen from 68.5% to 56%, according to data released by China's National Bureau of Statistics (International Trade Administration, 2023). Recently, however, a combination of energy crises, conflicts, and droughts affecting domestic hydropower generation and associated grid balance disruptions has led policymakers to take a more cautious approach to phasing out coal power.

The study of International Trade Administration (2023) states that "although China has diversified its energy supply and begun to replace fuel oil and coal with cleaner fuels, they still represent a relatively small share of the Chinese energy mix. However, the use of natural gas, nuclear energy and renewable energy is constantly increasing.”

In summary, we can say that so far China has almost always solved the economic problems it has faced on time. Moreover, with forward-looking strategic planning, it has achieved that it has now become an indispensable player in the clean energy transition on a global level. It invests more in renewable energy developments and installs more renewable capacity than the rest of the world combined. However, the annual 8-10% increase in energy demand poses challenges in terms of guaranteeing security of supply that the Western world has not faced for a long time. It has to solve all this in a World burdened with energy crises and war conflicts, in which it itself is sometimes in the crosshairs, at least at the level of rhetoric. In any case, China feels threatened and now appears to be turning for a time to coal, its only truly abundant source of domestic energy. Perhaps this explains the fact that China is also looking for a long-term solution to the use of coal. With the development of ultra- or zero CO2-emitting clean coal technologies, coal-fired power plants can also be a means of greening the Chinese energy sector not implying an irresolvable contradiction between the energetic utilization of coal and carbon neutrality. However, we hope that peace will return to all parts of the World and that greening can once again come to the fore without risking the security of supply.

6. References

Flora Champenois, Lauri Myllyvirta, Qi Qin, Xing Zhang (2023) China’s new coal power spree continues as more provinces jump on the bandwagon. Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, https://energyandcleanair.org/publication/chinas-new-coal-power-spree-continues-as-more-provinces-jump-on-the-bandwagon/

International Trade Administration (2023) Energy, In: China – Country Commercial Guide. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/china-energy

Michael O'Boyle (2023) Accelerating Clean Energy In China: Q+A With Expert Jiang Lin. https://www.forbes.com/sites/energyinnovation/2023/02/27/accelerating-clean-energy-in-china-qa-with-expert-jiang-lin/

Nikit Abhyankar, Jiang Lin, Fritz Kahrl, Shengfei Yin, Umed Paliwal, Xu Liu, Nina Khanna, Qian Luo, David Wooley, Mike O’Boyle, Olivia Ashmoore, Robbie Orvis, Michelle Solomon, Amol Phadke 2022) Achieving an 80% carbon-free electricity system in China by 2035. iScience, Volume 25, Issue 10, 105180, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589004222014523