Why do some climate treaties work, while others don’t?

Abstract

The shortcomings of climate agreements concluded over recent years and decades are hard to miss. In many cases, the commitments made are insufficient, while adequate commitments are unenforceable, and several important decisions are postponed. All this may seem surprising in the light of the fact that in the early days of what we now know as environmental and climate protection, agreements and examples of international cooperation were reached that successfully sought to address important issues.

While the lack of accountability and coercion makes a major contribution to this rift, it is not the only explanation. In addition to coercive force, economic and strategic interests also play a major role in the slow pace at which the complex problem of climate change is being addressed. There is also a lack of clear, precise and unambiguous expectations; countries struggle to handle abstract, obscure and elusive proposals. Mankind is in possession of the intellectual and economic basis to solve the issue of climate change and, given time, we can achieve the same visible successes as in the field of ozone protection. If we are to remain grounded in reality, the pace of various parallel processes will not and cannot be identical.

Introduction

Annual UN climate summits known as so-called COP conferences have been subject to heavy criticism. In the past years, this has focused mainly on the hypocrisy of world leaders taking private jets to remote parts of the planet to discuss what should be done to protect the climate. Many also criticize the Paris climate agreement and international treaties preceding it for apparently having no real impact due to their lack of coercive force. Are private jets and the lack of enforcement the true problem? Have these agreements genuinely failed? These are some of the questions we seek to answer in the present analysis.

COP

The COP series, officially known as the United Nations Climate Change Conference was launched as the successor to the Earth Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The first in the line of COP conferences took place in Berlin in 1995 and, since then, the event has been organized every year (except 2020).

Already widely publicized in the 2010s, the event began receiving even more attention in recent years as climate awareness has steadily increased around the world. However, this attention has tended to cast the COP in an unfavorable light; the best-known example of this negative publicity is the alleged hypocrisy of world leaders traveling to climate conferences on their private jets, this contributing to climate change themselves. In reality, this is rather a boisterous accusation than a substantiated observation; if COP conferences were to produce comprehensive agreements that significantly curb humanity’s GHG emissions and these would require the presence of world leaders, we could rightly say that they are worth the cost. It should therefore be examined whether such agreements are being reached.

The experience of recent years most definitely paints a different picture. COP 21, held in Paris in 2015, resulted in one of the best-known climate agreements, which has been attacked by critics on many points. The document’s volatile and vague text is itself telling. The 196 signatory countries pledged to reduce their carbon emissions “as soon as possible” and to keep global warming “well below 2 degrees Celsius” compared to pre-industrial levels. In addition to the wording of the text, its content is also indecisive and unspecific. Member states are to set their own emission reduction targets, without constraints and on a voluntary basis. Not only is there no minimum rate of reduction, but the Agreement fails even to specify the date the target is to be set. Many argue, however, that the greatest shortcoming of the Agreement is that it has no binding force and if a member state fails to meet its reduction target by the deadline, there are no consequences apart from, perhaps, some embarrassment.

The infirm package of measures is performing as would be expected.

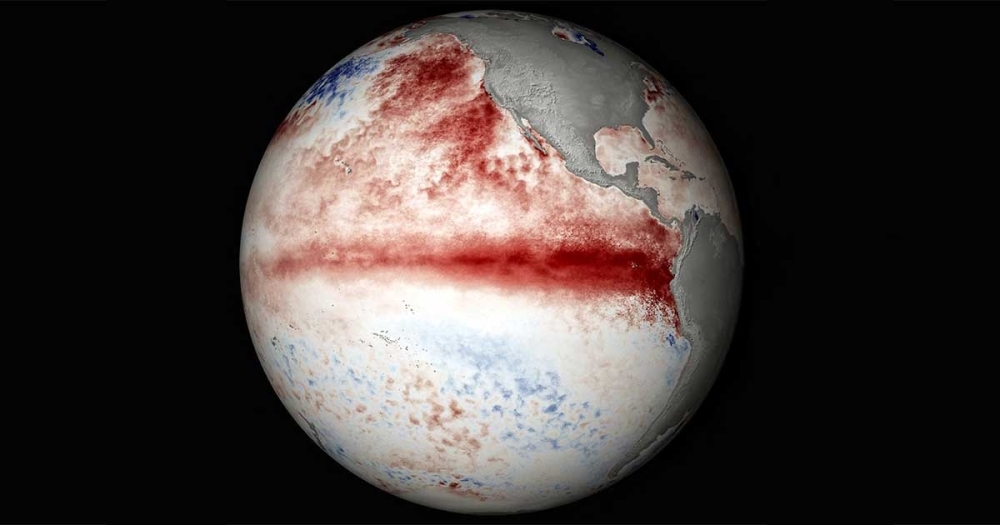

Source: Climate Action Tracker, December 2022

The map above classifies countries according to various indicators, each of which is designed to measure the ambitiousness of a country’s commitments, the extent to which its legislation is aligned with the targets set, and the transparency and clarity of domestic regulations, i.e. overall contribution to keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. Yellow indicates an “almost sufficient”, orange an “insufficient”, red a “severely insufficient” and dark gray a “dangerously insufficient” contribution. No data is available for light gray and white countries. Although the original map legend includes the color green, indicating sufficient contribution, it is clear that even the “almost sufficient” category features only a handful of countries, while no single one fits into the “sufficient” category.

The conferences held in the years following the 2015 COP were linked in some way to the Paris Agreement; they reaffirmed its significance, made new proposals to achieve commitments and supplemented the 2 degrees Celsius target by adding the necessity of keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius “if possible”. In reality, however, no significant progress has been made.

The 2016 COP came under heavy criticism for allowing fossil fuel lobby organizations and the World Coal Association to attend the conference as observers. The event was also perceived in the media as strong on rhetoric but weak on making genuine headway.

The 2017 conference sought to set out the way forward for the implementation of the Paris Agreement, adopted two years earlier. COP 23 also resulted in a more tangible outcome than usual, the establishment of the Powering Past Coal Alliance. The Alliance, joined by Hungary in 2021, was formed with the participation of states, cities and corporations with the aim of phasing out coal. Members seek to remove coal from power generation by a set date (2025 in the case of Hungary and 2030 at the latest for all member states), except for power plants where carbon capture and storage is in place. While it will be a few years before the results of the agreement can be evaluated in any meaningful way, it can be said that this COP went beyond rhetoric and reaffirming the Paris Agreement.

COP 24 was also focused on implementing the objectives of the Paris Agreement; however, many issues were deferred to the next conference. COP 25, held in 2019, was not a resounding success either; some urgent issues, such as the development of a carbon quota trading system, were postponed to the following year. Because of the cancellation of COP in 2020 due to COVID, this ended up being a two-year wait.

COP 26, held in Glasgow in 2021, went some way beyond footnotes to the 2015 Paris Agreement but still failed to provide the compelling force to deliver on commitments. The conference agreed that efforts should be made to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius, not just 2 degrees Celsius, below pre-industrial levels. Many countries have made commitments to achieve carbon neutrality with different deadlines.

Over a hundred countries have pledged to end deforestation by 2030.

Among them were Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Indonesia, the three countries with the largest area covered by tropical rainforest. However, tangible, exact, verifiable and enforceable commitments were again lacking this year. Green activist Greta Thunberg summed up the results of the conference succinctly: “bla, bla, bla”.

Although COP 27 in 2022 also received its share of criticism, a decision was taken that many called the most important move to tackle climate change since the 2015 Paris Agreement. A proposal was made to create a loss and damage fund to provide financial and humanitarian assistance to areas most affected by climate change in the event of a disaster. The fund is intended to help developing countries that contribute least to climate change but suffer most from its consequences; typically for COP, however, concrete measures remain unclear. The details – such as which countries are to contribute to the fund and how much, what will these payments cover and exactly which countries will benefit from these resources – are still to be worked out. Despite this, the agreement to set up the fund is an important message to developing countries.

Producing little in the way of new achievements and no binding commitments since 2015, COP conferences have rightly earned the world’s dislike, and as global emissions continue to rise, even the private jet cliché seems to be a valid criticism. The good ideas being put forward seldom translate into real commitments and are often deferred to the following year. Something perhaps more than coercive force is therefore missing from measures linked to the COP.

A positive example: ozone conventions

The ozone layer is the part of the stratosphere where the tri-oxygen ozone molecules are more abundant (although their proportion is still almost negligible) than in the rest of the atmosphere. This layer plays a key role for life on Earth by filtering out most harmful wavelengths of ultraviolet radiation, thus preventing it from damaging living organisms.

Research published in 1974 has shown that members of a group of compounds known as chlorofuorocarbons, known as CFCs, damage the ozone layer by reducing its concentrations, thus allowing more harmful radiation to reach the surface of the Earth. These compounds have been widely used for insulating buildings, refrigeration, packaging and as propellants for sprays. In 1985, an “ozone hole”, or more precisely a sharp drop in ozone concentration, was discovered over Antarctica. It was later proven to be linked to anthropogenic CFC emissions.

This was the beginning of an international coalition of unparalleled effectiveness that today’s climate activists can only envy. Together, the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer resulted in CFC production being halved by 1987. In 1990, the Montreal Protocol was extended, requiring the phasing out of CFCs by 2000 in the case of developed countries and 2010 in the case of developing nations.

Today, a total of 198 countries – including all UN member states – are party to the Convention. Since the Protocol not only banned the production of CFCs by signatories but also CFC trade with non-signatories, there are no major players left with an interest in opting out.

Rapid, decisive and coercive action has meant that the “ozone hole” seems to be regenerating, with the ozone layer expected to regain its original density sooner or later, depending on the part of the atmosphere. Over areas far from the poles, it could return to its original potential by 2040, while the regeneration is expected around 2045 over the Arctic Circle and by 2066 over Antarctica. While it is easy to argue for the success or failure of an international agreement, an ozone convention that has resulted in the verifiable recovery of the ozone layer is an undoubted success.

What is the difference?

COP conferences have been held almost annually for decades, largely producing more pledges than results. By contrast, a convention signed 36 years ago and extended three years later has achieved its goal and can deliver visible solutions on an issue that is vital for the entire planet. What are the weaknesses of the former and the strengths of the latter?

One could argue that ozone depletion has serious short-term health consequences for humanity and the planet as a whole, so there was no need for further motivation to ban CFCs. However, this is no longer the case as air pollution, global warming and climate change in a broader sense have been shown to cause enormous damage to public health and wildlife, yet decisive action is delayed. The solution is to be found elsewhere.

The first and most obvious answer is the oft-mentioned lack of coercive force. Based on the Paris Agreement, COP negotiations in recent years have made no attempt whatsoever to impose strong regulations, strict deadlines and sanctions. The Montreal Protocol, on the other hand, has set out precisely what it expects of its signatories, set specific deadlines for its targets and imposed trade sanctions on non-compliant states. While this certainly is an important part of the solution, the problem is multi-faceted.

The second relevant difference between the two sets of problems is the economic and strategic interest in taking or avoiding measures. Of course, there was also a huge market for CFC products and a strong economic interest linked to these industries. However, there are two major differences between CFCs and sectors closely linked to climate change. The first is the size of the two sectors; although the market for CFC products in the past could be considered large, it was incomparable in size to energy generation, transport, industry and agriculture. Far more important economic interests would be harmed if a sudden and drastic change in the structure of the latter were to occur.

The second difference is the potential to replace harmful substances and processes. Although CFCs and other ozone-depleting chemicals have been banned in most of the world, it is still possible to buy deodorants and refrigerators or to insulate our houses; sectors have been able to navigate the global market like cruisers and adapt to the ban of one element of their activity. Energy, transport, industry and agriculture, on the other hand, are like aircraft carriers: they are unable to change direction swiftly and drastically. There are, of course, technologies that can improve sectors most linked to climate change in terms of environmental impact; these, however, cannot completely replace technologies such as coal burning that have been used for centuries, often millennia, in a few years. The infrastructure and tools developed by humanity are tailored to polluting and climate change-inducing processes. This can and must change slowly, but we cannot hope for a sudden success like the Montreal Protocol.

The third major difference between ozone protection and climate protection is the specificity of responses to the problem. Regulations aimed at restoring the ozone layer precisely specified the chemicals whose production and trade is to be banned in order to achieve the desired outcome. At climate conferences, however, it is already considered specific to be one step more precise than the immeasurably complex “reduction of emissions” and to prescribe, or rather propose, a reduction of coal burning.

However, even such a “concrete” proposal raises more questions than it answers. What should be done with power plants that can only run on coal? What should be done by countries whose energy mix is dominated by coal? Is it enough to start by abandoning the use of lignite and brown coal? Is there a way forward to provide sequestration capacity instead of export? International negotiations are sluggish processes, and their results are interpreted by equally sluggish governments that are unable to work efficiently with ambiguous, formulaic and vague proposals.

So while climate agreements cannot be expected to deliver the same rapid and spectacular results as ozone conventions, this does not mean that we should give up on fighting climate change.